On Developing Our History

It’s 7:30 in the morning, and Dr. Lordan is writing an email in response to an invitation to the Golden Anniversary Reunion of his high school class. 50 years ago, the wise, well-spoken Dr. Lordan was a senior himself– in the same position as the students he’s teaching today.

As Lordan finishes up his morning work, he heads to his first period class. This year, he’s teaching senior theology classes, both Dominican Spirituality and World Religions. In previous years, Lordan has primarily taught history classes. Even with the abrupt switch from history to theology, Lordan has no problem adjusting.

When he first started teaching at Fenwick in the autumn of 1991, Lordan taught the New Testament theology class. Since then, he has taken up mostly history classes, including Western Civics, World History, Economics, and American History.

Aside from teaching theology, spirituality and religion play a large role in Dr. Lordan’s life. He has been part of the Dominican laity for five years. The cross students see him wearing everyday is the symbol of the laity– something Lordan displays with pride as he teaches his classes about Dominican Spirituality.

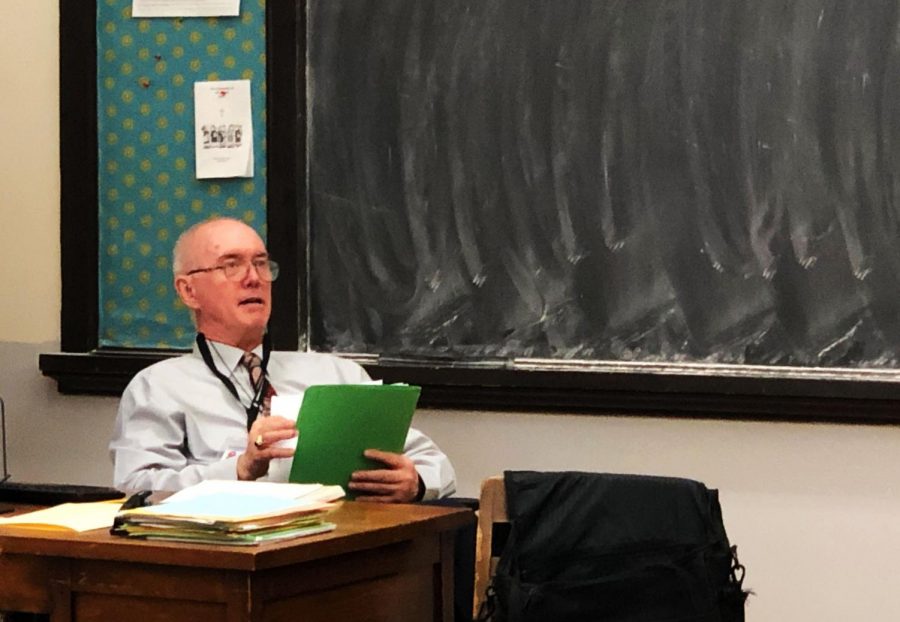

Lordan welcomes his first period students as they pile into Room 36. As everyone settles in, Lordan starts with a rundown of the class. The schedule is always organized, but more importantly, incremental. He makes sure that the class is pieced together, instead of being dominated by one form of teaching. Lordan specifically structures his class in 15-minute blocks, as he believes students are able to absorb information more thoroughly than if he were to present material for the full 45 minutes.

Lordan begins class with a review of their notes from the previous day. He does this every day, as he believes that students retain information more easily when it is presented to them in the same context each time. Lordan attributes this to the stimulus-response theory, that states behavior is conducted by an external impulse.

He learned this method of teaching when he was completing his doctorate in Educational Philosophy and Educational Theory at Boston College. All of Dr. Lordan’s students can attest to the presence of philosophical and psychological concepts in his courses. He seamlessly weaves topics like Erikson’s stages of life and Freudian theories into lectures, providing students with reasons for why humans act the way they do and why history is what it is.

Shifting from his desk chair to the chalkboard, Lordan begins a 15-minute lecture on early Christianity. He adds in a small life lesson, as he usually does, about history. He notes that one studies history to understand the past and shape the future. The philosophy is one Lordan lives by, and tries to pass onto his students. His students definitely notice that history greatly influences each class, with small historical lessons intertwined with each topic.

One of Lordan’s goals with each class is to provide students with a strong background on historical perspective in order to understand smaller scale aspects of religion. He wants his students to know about how the early crusades affected the later form of Christianity, or how the Dark Ages influenced the upbringing of different orders of priest.

Moving onto the next block of 15-minutes, Lordan tells students to clear their desks in order to take a short quiz. He gives quizzes about twice a week as a review of the words he has presented in class. Quizzes offer students the opportunity to memorize the spellings and meanings of words that will appear on tests. Lordan always takes off points for misspellings, as he believes that students retain more information when they are corrected for their mistakes. He reminds his students that it’s more difficult to erase a bad habit than to start a new one.

Lordan describes the human mind as a computer data bank. As he lectures, students open a file, put information in, and put it back into storage. With daily reviews and quizzes, students are able to restore files, correct errors, and perfect the system. Lordan’s class is structured with the students in mind; he knows how they function, how they react, and how they learn best. As Faculty Mentor at Fenwick, he helps new teachers adjust to their classrooms and works with older faculty members on retirement.

Lordan ends the class with a small anecdote. He asks students to imagine the primitive cavemen, huddled around a campfire, discussing things in the only way they know how. One of the cavemen leaves the fire, setting out on the vast land ahead, going off on a great adventure. Dr. Lordan tell his students that, in this moment, they are the cavemen sitting around the fire, absorbing information and stories. When they are ready, they must leave the pack, taking only knowledge with them, bracing themselves for the experiences ahead.