Unrest Prompts Early Dismissal

Illustration by Lillie Gihl

On October 5, 2018, at approximately 12:23 p.m., hallways fell silent, classes ceased to be taught, and every student froze. Principal Groom’s voice echoed throughout the stairwells on the intercom with every ear absorbing the words which proceeded from his mouth with intensity. Rumors of an early dismissal had been wandering about the Fenwick community, as a spirit of uncertainty rested upon each student. Even school wide Schoology posts titled “Van Dyke Verdict Alternative Transportation Plan” foreshadowed the abrupt turn of events.

The Trial: Rewind to night of October 20, 2014. 17-year-old Laquan McDonald is pursued by two dispatched policemen of the Southwest territory after witnesses report him breaking into cars and threatening the owners with a knife after confrontation. Officers Thomas Gaffney and Joseph McElligott take notes from witnesses, follow their directions, and immediately locate McDonald as he travels on foot. Tensions hastily rise between the officers and McDonald due to proximity and the unpredictability of what the next move may be. McDonald gashes the front tire of the squad car with a knife.

Adhering to protocol, the officers request backup and Officers Joseph Walsh and Jason Van Dyke are on site less than a minute later at 9:56:56 p.m. Officer Van Dyke exits his car, draws his gun, and makes contact with Laquan McDonald at 9:57:28 p.m. McDonald walks forward in the same direction of the officers with a knife in his right hand. At 9:57:36 Van Dyke opens fire, bringing McDonald to the ground. Van Dyke releases a total of 16 shots in 14 seconds.

On April 15, 2015, the Chicago City Council agrees to pay the McDonald family a five million settlement to close the case. Later that year, journalists request dashcam footage of the shooting, and are denied by the Chicago Police Department. On November 19, 2015 Judge Franklin Valderrama orders the video to be released. In a moments time Officer Van Dyke is charged with first-degree murder.

The Verdict: After years of going back and forth between the defense and the prosecution, closing statements were made before the jury. While the prosecution argued that there was substantial “evidence of intended murder,” the defense supported the protection of the acting officers and of the following statement:”This was a tragedy that could have been prevented with one simple step. At any point throughout that 20-something minute rampage had Laquan McDonald dropped the knife, he’d be here today,” (Lead Defense Attorney Daniel Herbert).

On October 5, 2018, at approximately 1:53 p.m., Officer Jason Van Dyke was found guilty of second-degree murder and was convicted of 16 accounts of aggravated battery, one for each shot fired at Laquan McDonald. He faces possible consequences of probation through 20 years in prison. Additionally, he faces 6-30 years in prison per account.

What Everyone Prepared For: Riots. If the jury had reached a different, perhaps lesser verdict, the city of Chicago was expected to experience extreme backlash. In anticipation, the Chicago Police Department prepared for the worst. They predicted violent outbreaks within city streets, the looting of local stores, physical altercations with police officers, human blockades, car theft and city wide protests that would detour and delay the traffic flow.

In 2014, Ferguson, Missouri faced a comparable situation. A teenage boy was fatally shot by a police officer. The officer was found not guilty. Local rioters set fire to buildings, incinerated cars, shattered storefront windows, harassed police officers and released over 150 gunshots citywide.

In an effort to avoid the repetition of such dire consequences in Chicago, the downtown area was flooded with police officers on horseback, bike, foot, and in cars. They were stationed on almost corner of the city. Schools all over the Chicagoland area dismissed students from school for their protection, and lockdown protocols were followed in the hours preceding the verdict’s release.

October 5 was not by any means a lucky afternoon to skip a chemistry test. It was a time to seek safety, become aware, and reflect on a very sensitive matter. The Fenwick administration, along with many other organizations and institutions made the executive decision to cease all activity for the protection of families across the city.

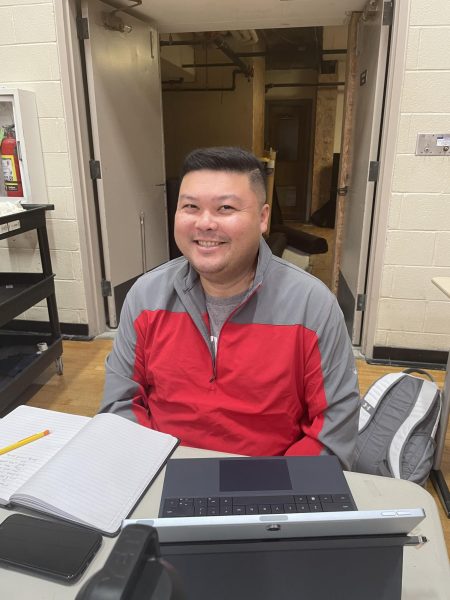

Dean Moland comments that the first priority of the administration was to protect the students, saying, “Whenever it comes to children’s safety, we must always plan for the worst case scenario.” Fenwick had been conversing with the police department, as well as keeping tabs on social media in the days preceding the verdict, and concluded that the decision to dismiss students early was absolutely necessary— a decision behind which the administration remains.

The nation’s political climate seems to be increasing in volatility every day. Principal Groom cites the school shooting epidemic and the #MeToo movement as evidence of such volatility, but encourages students to use these issues “as an opportunity to reflect on our beliefs and determine what we can do individually and as a community to help move humanity to a place of peace and understanding.” As a parent and leader of an entire student body, Groom understands the delicacy of such politically-charged issues.

He holds the conviction that a sense of understanding is of the utmost importance, saying that “Once people come to a point of understanding, they have begun to think for themselves in a rational and logical way.

“I believe that once this happens, barriers between people are broken down and we arrive at a better place.” It is with this ideal in mind that Fenwick students and administrators continue their educational efforts.