Parting is Such Sweet Sorrow: A Tribute to the Dying Art of Valentine Writing

A vibrant red bowl holds fluffy white kernels with little smiley faces. The illustration fills a delicate piece of cardstock. “I’m gonna pop a corny question: will you be my valentine?” I chuckled to myself as I dug even deeper into the shoebox that overflowed with hundreds of letters, notes, and Valentine’s Day messages my grandmother had carefully curated over the years. Some of the notes had paper flaps, ornate pop-outs and sliding surprises. I leafed past a moving arm of a particularly jolly picket fence painter, a smiling ice cream cone that exclaimed, “I’ll melt for you!” and an image of two kids with shiny silver space helmets, a tribute to the Space Race culture that even permeated Valentine’s designs. As a longtime teacher, my grandma has become somewhat of an expert in Valentine exchanges, and her impressive collection now serves as a window into the past.

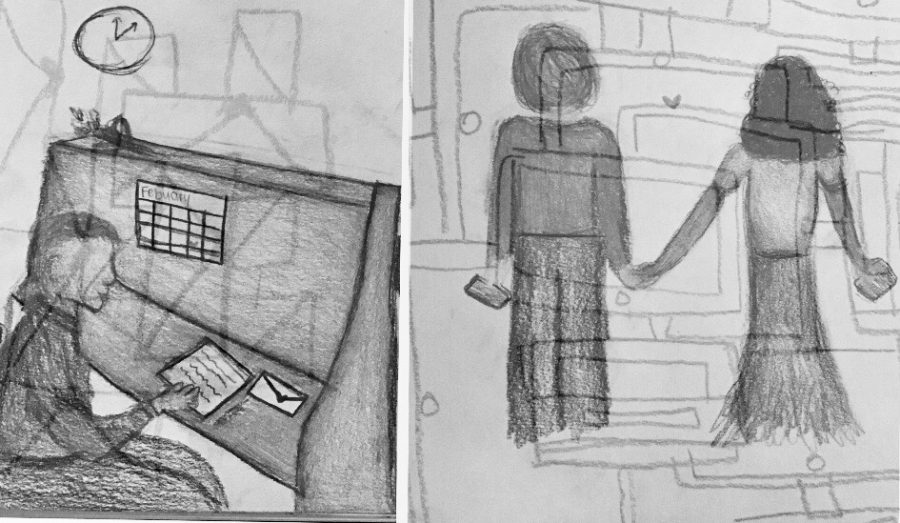

Now, as teenagers celebrating Valentine’s Day, we can look forward to run-of-the-mill cards that seem more like advertisements for movies and TV shows (I know we’ve all seen the “Wow, you’re MARVEL-ous,” complete with images of Spider-Man and Tony Stark), a few measly candy packets from our most festive classmates, and maybe, just maybe, a text from someone special. “Hey what’s up?” or “Happy Valentine’s Day!” (Even then, capitalization and punctuation use are a real toss up.) It is therefore no surprise that as I examined my grandmother’s cards, whether from her students, family members, or even potential suitors, I could not help but wonder whether my generation had lost something along the way.

The art of letter writing, once a necessity for social and romantic connection, is dying a slow, painful and belabored death. According to a CBS News poll of 1,717 adults in September 2021, only 31% of individuals had written a personal letter within the last year. Even more shocking is the fact that 22% of adults aged 18 to 44 have never written a letter in their life. Alternatively, according to a survey by nonprofit Common Sense, almost 62% of teens aged eight to eighteen report four hours of screen time a day. More shockingly, up to 29% of those surveyed used their phones for more than eight hours a day. Yes, it is clear that letter writing is a dying art, and to blame is the guiltless behemoth, the merciless killer, the unremorseful beast: social media.

The stark reality of teen life in 2022 is that cultivating a social life requires both face-to-face interactions in and outside of school combined with a nearly constant engagement on various social media platforms and the maintenance of innumerable text conversations and group chats. Often a suffocating reality, the dynamic of constant connection and immediate communication leads to the perception of instant gratification and transience in our relationships. Text someone and they text back within minutes, if not seconds. Then, there is invariably a mess of unwritten rules: Oh no! You responded too quickly, too slowly, with too many words, with too few. Often, texts employ more emojis than words, opening a Pandora’s box of possible and ever-changing interpretations within those tiny icons.

Yes, I admit, there is a definitive convenience to a crying laughing face when your friend cracks a joke, but at some point, no animated facial expression can capture the beauty of the written word. Imagine Renaissance love poet Edmund Spenser sitting down by the candle light, dunking his feather quill with obsidian ink and beginning to write: “For love is a celestial harmony/ Of likely hearts compos’d of stars’ consent.” Now, disregarding the blatant anachronism, imagine him trying to text this same passage as a Valentine’s Day message.

Surprisingly, the benefits of letter writing are not just a nostalgic sentimentality for bygone eras, but are fundamentally linked to the psychology of human interaction. As chronicled in Psychology Today, the physical act of writing triggers stronger neural encoding and capacity for memory retrieval. So while authors and poets have long sung the praises of “putting pen to paper,” there is an inherent biological benefit in this aphorism beyond its dramatic value based in neuroscience.

When I asked my grandma about her Valentine’s Day messages, she told me stories about her favorite day of the whole school year, when her students would approach her desk with proud faces and handwritten cards adorned with loopy script and hand-drawn pictures. After all, what better way to show someone that you care than to put in precious time, effort and thought into writing them a message?

Our generation is incredibly lucky to have grown up with new communication methods enabled by developing technology, but it is equally essential to look to the past. It is our responsibility to preserve and hopefully revive the emotion-laden and unequivocally romantic art of letter writing for Valentine’s Days to come. So Friars, the next time you get tired of the oppressive cloud of SnapChat or Instagram, consider writing your friends a letter. Yes, you might get a few strange looks at first, but ponder this: you will be joining the dwindling ranks of the courageous, ragtag militia of letter writers. And we need YOU!