An Unstoppable Force: Alumna Continues On the Road to Tokyo 2020

At 16 years old, in her sophomore year, Mary Kate Callahan never expected to be sitting in depositions and meeting with lawyers. She couldn’t have imagined hearing an adult say to her face that disabled athletes don’t deserve the same opportunities as their teammates. Everything changed when her advocacy for equal athletic opportunity spawned a lawsuit against the IHSA. Now, at 24, Callahan is an elite paratriathlete and Ironman, and she couldn’t picture herself doing anything else.

Mary Kate Callahan ’13 has been in a wheelchair for as long as she can remember—disabled at just months old. The La Grange native grew up alongside able-bodied friends and classmates. Like everyone else, she decided to get into athletics and thrived despite her disability. In first grade, she started swimming competitively, and from then on sampled every other sport on the books. From skiing to wheelchair basketball, Callahan was just as active as any other kid.

It was during her time at Fenwick that she realized, however, that things were not as fair as they seemed. In 2009, at the start of her freshman year, Callahan joined the swim team. She went to all of the same grueling practices and put in the work like everyone else, but at a certain point of the season, every disabled athlete was cut off, including Callahan.

It was after the school year that she found out other states had more options for athletes like her. Friends from outside of Illinois helped her realize that there were opportunities in thirty-four other states for disabled athletes to continue their seasons.

With the support of her family, Mr. Thies, Mr. Curtin and the Fenwick administration, Callahan met with the IHSA to discuss setting new qualifying standards for athletes so their seasons could continue into the state championships. Unfortunately, she was met by much resistance. The only viable option seemed to be a lawsuit against the association, so with the backing of the Equip for Equality advocacy group, Callahan filed a suit.

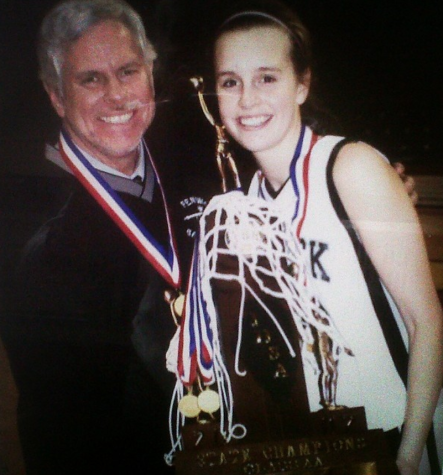

Much of her time as a high schooler was spent splitting her priorities between regular life and being embroiled in a lawsuit. Even so, Callahan never considered it a burden. Mr. Groom, principal during her time at Fenwick, remembers the sense of urgency—the rush to wrap up the issue before the start of Callahan’s last season, all while adhering to the protocol of IHSA dealings. Ultimately, there couldn’t have been a better result. The settlement reached allowed Callahan to score points for the state championships, at which she won first in the 100-meter breast and then second in both the 100 and 200-meter freestyle events. She spent her senior year as captain of the swim team.

On behalf of Fenwick, Mr. Groom offered a sentiment of gratitude on behalf of Fenwick: “We appreciate the example that she set for her classmates and future Friars. Her perseverance and determination [were] unparalleled. We are definitely a better place because of her.”

It could be speculated that a teenager in Callahan’s shoes would be in over his or her head. However, throughout the entire conflict, she had no regrets. Instead of being discouraged by the IHSA’s efforts to stifle athletic opportunities, Callahan saw it as an opportunity to “educate them on what the disabled can do, not just in athletics, but across the board.”

Her motivation is far more noble than what would be expected of a person her age: to prevent the next generation from “feeling like they were being pushed to the sidelines because of their disabilities.”

Aside from the lawsuit, another turning point in Callahan’s life was her introduction to triathlons. When still in high school, a past coach of Callahan’s proposed that she try one—to which she responded that her coach was “out of her mind.” After completing her first one, however, she was hooked for good.

“I love seeing what the human body can do,” she says. People race for all sorts of reasons. Callahan’s is that she thrives off of competition, and, over all else, because it is enjoyable.

“The second I stop having fun is the second I’ll start questioning if I want to keep doing this.” Fun, she says, is what makes the soreness, the early mornings and the hours of training worth it.

Callahan works in Human Resources at Motorola Solutions in conjunction with her athletic regiment. Between the two, she feels like she’s living the “Hannah Montana lifestyle.” Sometimes, she says, she goes from the pool right to work with wet hair. She always has a bike helmet with her. Though such a life seems hectic, Callahan is a master at balancing her priorities.

In the 2016 Rio games, Callahan was unable to compete; all of the medal events for men and women excluded her qualification. “[My] dream got ripped out from under my feet, gone in a matter of a day,” she remembers. That exclusion from the Rio Paralympics did, however, prompt another journey for her.

It was at that point that Callahan decided to keep herself busy by competing in an Ironman. People were concerned for her, she remembers. Racing for thirteen hours as such a young athlete seemed daunting; even so, she has no regrets. “Something in me said that now was the time,” she says. Callahan was right: she gained the highly sought-after title of Ironman.

Since Rio, the classifications for Paralympic competitions have been expanded, and Callahan is well on her way to qualifying for the 2020 Tokyo Paralympics. This journey has brought her into the public eye, including that of Gatorade, which included Callahan in its #MyFuelMyJourney campaign.

She knows that in the future, sports may no longer be an option, but she will always be an athlete no matter is she is or is not competing. “You only get one body,” says Callahan, “and I put mine through a lot of rigor every day.”

If athletics ever exit the picture, Callahan still has an extensive network in philanthropy to keep her busy. As a mentor through Dare2tri, a board member of USA Triathlon and an event organizer for her family’s Claddagh Foundation, Callahan has dedicated herself to connecting with the next generation. The foundation’s main goal is to help paraplegics like Callahan to find their “new normals” through funding spinal cord research and providing grants for paraplegic resources.

It’s all about allowing a disabled person to live independently, Callahan explains.

She remembers being five or six years-old and figuring out for the first time how to transfer herself into a car. “If my parents didn’t let me figure out how to do that for myself, I couldn’t be moving a mile-a-minute like I am now.”

The little things matter most, in Callahan’s eyes. Whether it be giving a wheelchair-bound mother an adapted car so that she can drive her kids to soccer practice, or giving a child a bike so he or she can ride around the streets with the neighborhood kids, the Claddagh Foundation is dedicated to improving disabled people’s quality of life in all aspects. The foundation has raised over 2.5 million dollars, and recently celebrated its twenty-third golf-outing.

To anyone struggling with adversity today, Callahan has valuable advice: “Never be afraid to stand up for what you believe in—you will be surprised to see how many other people will stand behind you. There are things that aren’t easy, but that doesn’t mean they aren’t worth [pursuing]. Never, never, never give up.”